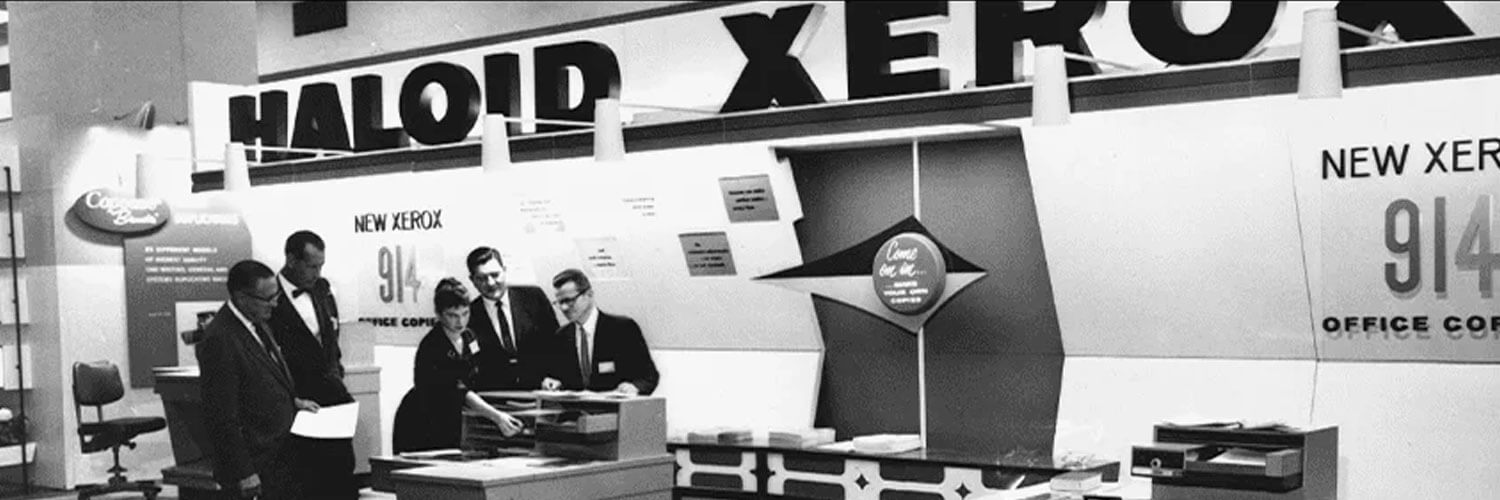

You’re showing your age if you’ve ever had someone ask you to “Xerox” a document. But beyond the nostalgia, there’s a powerful marketing lesson buried in that seemingly simple phrase. First introduced in September 1959, the Xerox 914 was one of the boldest technological gambles of its time, quickly transforming from a clunky, expensive machine to a household name—and a verb synonymous with copying. This shift didn’t just happen by chance; it was a result of brilliant marketing that turned a product into something more than just a tool—it became the symbol for its function.

Weighing in at a hefty 648 pounds, the Xerox 914 was no lightweight—it occupied the floor space of a large desk, churned out copies at a sluggish pace of just six per minute, and carried an eye-watering price tag of $29,500 (equivalent to nearly $300,000 today when adjusted for inflation). Yet, despite its limitations, the Xerox machine quickly found its place in offices and businesses across America, and it wasn’t long before people started using “Xerox” as a verb, much like how people say they’re going to “Kleenex” their nose or “Band-Aid” a cut, regardless of the brand they’re actually using.

This phenomenon isn’t unique to Xerox. In fact, the power of brand names transforming into verbs is a testament to how deeply a product can penetrate public consciousness, becoming the default term for an entire category of goods or services. Take Google—the most iconic brand to become a verb in the 21st century. We don’t just search for something on the web; we “Google” it, even if we’re using a different search engine. Similarly, we don’t just order food through an app; we “Uber Eats” it, regardless of whether we’re using Postmates, DoorDash, or Grubhub.

Then there’s Zoom, which not only became the go-to video conferencing platform during the COVID-19 pandemic, but also became a verb in its own right. Now, when people say they’re “going to Zoom,” they might not even be using the actual Zoom platform. It’s become a generic term for video calls, much like how “Xerox” became synonymous with making copies.

But it’s not just about tech products. Think about Teflon—a brand of non-stick cookware that has become synonymous with anything that “won’t stick.” People talk about a politician having “Teflon” qualities when they seem impervious to criticism, regardless of whether they’re using the brand’s cookware or not. Jet Ski has similarly become a generic term for personal watercraft, even though it’s a brand name.

The lesson here for marketers is clear: when a product becomes so dominant, so synonymous with its function, it can effectively create its own category. But that kind of brand dominance doesn’t happen overnight. It requires strategic marketing, consumer trust, and sometimes, even a little bit of luck. If your product or service becomes so ingrained in people’s lives that they use your brand name as a verb, you’ve achieved a level of marketing success that goes beyond just sales—it becomes a cultural touchstone.

So next time you Google something, order through Uber Eats, or Zoom into a meeting, take a moment to appreciate the marketing genius that turned these brands into household verbs—and the legacy they’ve left behind, from the Xerox machine all the way to the digital age.

Go With The Flow

Go With The Flow